A pagan world: sermon on the fourth Sunday of Advent

By a Dominican Friar | 18 December 2024

“In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judaea …”

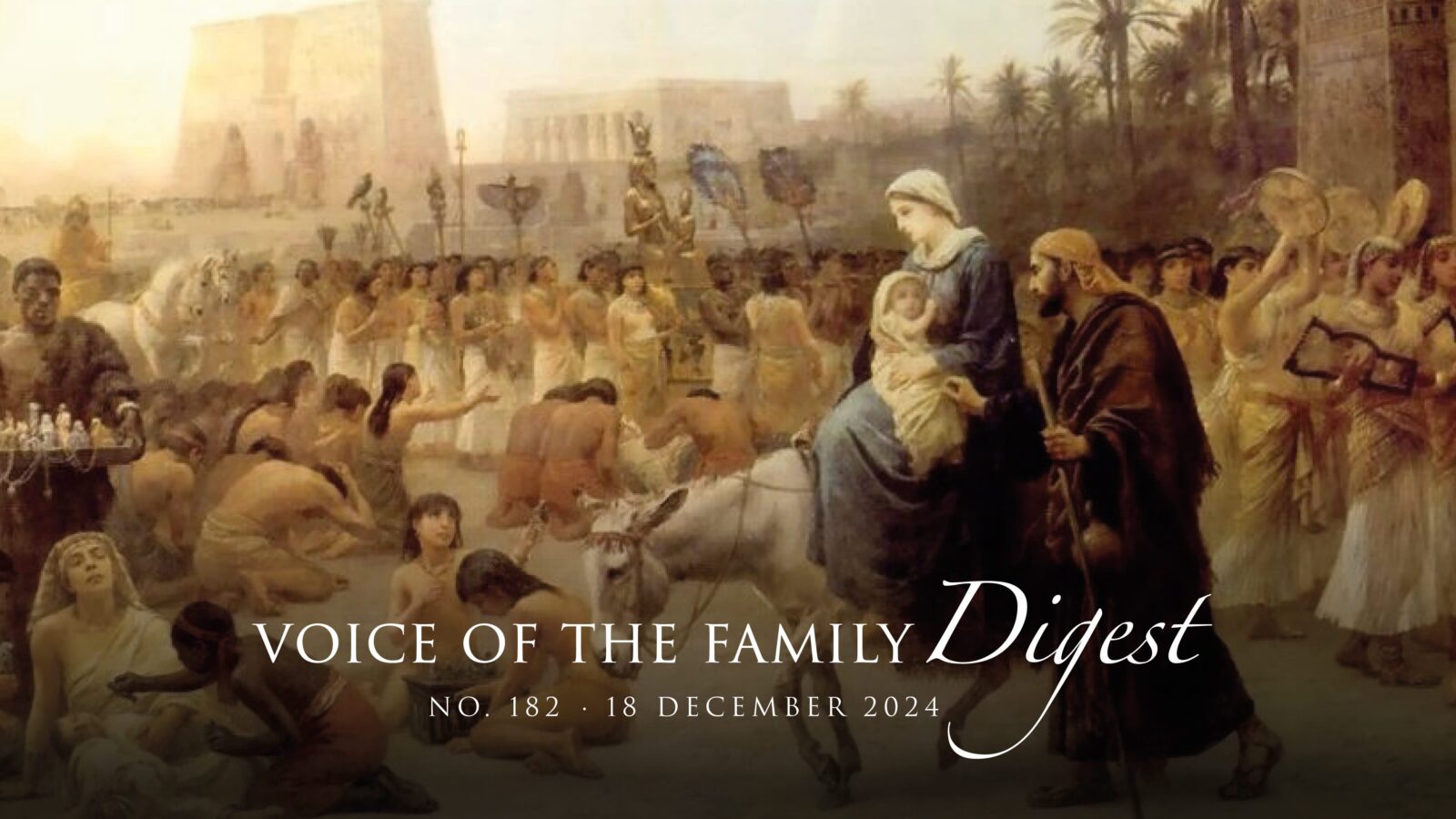

What was the world like before the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ? It was, very largely, a pagan world. True, the holy land of Israel remained, where the living God was worshipped; this was like an island in the midst of the sea. But as the first words of this Sunday’s gospel remind us, the holy land was itself under pagan rule, and had been for many a long year. First it had been the Babylonians, then the Persians, then the Greeks and Syrians, and now it was the Romans who were ruling over the holy places. And the Romans, of course, were pagans: that means that they did not acknowledge the true God, nor know about His revelation.

What kind of a world, then, did paganism produce? We can find an answer in the Old Testament, in chapter fourteen of the Book of Wisdom. It is a dark picture:

“They sacrifice their own children … They keep neither life nor marriage undefiled, but one kills another through envy, or grieves him through adultery; and all things are mingled together: blood, murder, theft and dissimulation, corruption and unfaithfulness, tumults and perjury, disquieting of the good, forgetfulness of God, changing of nature … For either they are mad when they are merry, or they prophesy lies, or they live unjustly … And although they lived in a great war of ignorance, they call so many and so great evils peace.”

In other words, in the pagan world before the coming of our Lord, there was much killing of children, born and unborn. There was frequent unfaithfulness between husband and wife. People didn’t know about the self-control they should have been practising before marriage. There was a general dishonesty in matters of business, with people out to cheat each other as far as they could. And there was even what the bible calls “changing of nature”, men acting like women, and women like men.

Underlying it all was a “forgetfulness of God”. As St Paul says, even though in their hearts everyone spontaneously knows that there is a God who made all things, the pagans suppressed this knowledge even from themselves so that they would feel more at liberty to yield to their desires.

Faced with all this, when He saw what mankind had done to the world that He had created for them, we might have supposed that God would withhold the Saviour whom He had once promised to send. But no: instead, He had pity on mankind. In His charity, the Father sent His only-begotten Son into the darkness of this world. He sent Him to be a light and a teacher, and to rebuild the bridge between earth and heaven, that Adam had broken down by his sin. And first of all, He sent St John to prepare the way, “preaching the baptism of penance for the remission of sins.”

Twenty centuries later, where are we? We live in a time when paganism has crept back. Again, there is a general suppression of the truth about God, and ignorance of His words. Again, there are the sins that follow from this ignorance: the killing of children, and the elderly; the defilement of the marriage bed; much lying and deception in order to make more money. And rather as the Jews of our Lord’s time felt themselves to be a small island in the ocean, so we may well feel beleaguered in an unbelieving world.

What will God the Father do now as He looks upon the world? He has no other Son to send to save us a second time. No: but His paternal charity is unchanged; to each man and woman who lives in the world, however unpromising their surroundings, He offers an opportunity to make a new beginning. God our Father is ready to send His Son again, not this time to the whole world, but to any individual soul who needs Him. All that is required today, just as in the days of John the Baptist, is penance: that a person turns from his sins, and asks forgiveness. Whoever does that in sincerity will most certainly “see the salvation of God”.